Abstract

This study examines the rise of ASEAN as a pivotal geopolitical and economic entity in a multipolar world, assessing its role in regional stability, trade integration, and strategic diplomacy. ASEAN has solidified its economic influence through initiatives such as the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), positioning it as the world’s fifth-largest economy with a combined GDP of $3.2 trillion. On the geopolitical front, ASEAN’s commitment to neutrality amid intensifying U.S.-China rivalry underscores its significance in regional security architectures, including the East Asia Summit (EAS) and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) However, ASEAN’s consensus-based decision-making model presents both advantages and constraints, as it fosters diplomatic cohesion but often delays responses to critical security and humanitarian crises, such as the South China Sea dispute. This paper argues that ASEAN’s sustained influence in an increasingly complex world order will hinge on its ability to deepen economic integration, enhance institutional responsiveness, and effectively balance great power competition while preserving its centrality in Indo-Pacific affairs.

Keywords: ASEAN Economic Integration, Geopolitical Strategy, Regional Stability, Consensus-Based Governance, Indo-Pacific Diplomacy

Introduction

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has emerged as a pivotal geopolitical and economic player in the Indo-Pacific. Founded in 1967, ASEAN has evolved from a loose coalition of five nations into a robust regional organization comprising ten member states, representing over 650 million people and a combined GDP of $3.2 trillion (Wrobel, 2019). Its unique model of regionalism, commonly referred to as the “ASEAN Way,” emphasizes consensus-based decision-making and non-interference in domestic affairs. While this approach has fostered stability, it has also been criticized for slowing institutional responses to security and economic crises (Purbantina, 2015).

Economically, ASEAN has positioned itself as a central hub for trade and investment through initiatives such as the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). RCEP, signed in 2020, is the world’s largest free trade agreement, encompassing 15 countries and accounting for 30% of global GDP (Bhasin & Kumar, 2022). These economic strategies have strengthened ASEAN’s global leverage and exposed the region to vulnerabilities, such as economic disparities and external market dependencies.

Geopolitically, ASEAN’s centrality in regional security is reinforced through platforms like the East Asia Summit (EAS) and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF). ASEAN’s diplomatic balancing act amid escalating U.S.-China competition underscores its strategic importance (Egberink & Van der Putten, 2010). However, the diversity of ASEAN member states in their foreign policy alignments presents challenges to unity and collective decision-making.

This paper argues that ASEAN’s sustained influence in an increasingly complex world order will hinge on its ability to deepen economic integration, enhance institutional responsiveness, and balance great power competition while preserving its central role in Indo-Pacific affairs.

Literature Review

The study of ASEAN’s geopolitical and economic rise has been widely explored through various academic lenses, focusing on its institutional mechanisms, economic growth, and strategic diplomacy. Existing literature predominantly addresses ASEAN’s regionalism, its economic integration strategies, and the challenges posed by great power competition in the Indo-Pacific.

ASEAN’s Regionalism and Institutional Mechanisms – Amitav Acharya (2014) introduced the concept of ASEAN’s “normative power,” emphasizing its role in shaping regional norms and values through the “ASEAN Way.” This consensus-based, non-interference approach has helped maintain regional stability but has also been critiqued for its slow decision-making processes. Donald Emmerson (2005) highlights that ASEAN’s reliance on consensus often leads to delayed responses addressing security and economic challenges. Similarly, Purbantina (2015) argues that ASEAN’s institutional framework remains constrained by a lack of enforcement mechanisms, limiting its effectiveness in crisis management.

Recent analyses indicate that ASEAN’s traditional diplomatic approach faces increasing pressure due to heightened geopolitical tensions. The ongoing South China Sea disputes and China’s growing assertiveness have raised concerns among ASEAN member states. For instance, the Philippines has emphasized its national interests in response to China’s regional actions (Reuters, 2025).

Moreover, ASEAN’s response to Myanmar’s ongoing crisis remains fragmented, highlighting challenges in maintaining unity. The bloc has excluded Myanmar from regional summits since the 2021 coup, but internal divisions have led to inconsistent approaches among member states (ASEAN Secretariat, 2024).

Economic Integration and Regional Trade Agreements – Trade agreements such as the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have reinforced ASEAN’s economic influence. Research by Bhasin & Kumar (2022) notes that RCEP, covering 30% of global GDP, strengthens ASEAN’s economic centrality but also exposes disparities among member states. Wrobel (2019) further explores ASEAN’s financial dependence on China, raising concerns about economic over-reliance.

Recent developments in trade relations indicate a shift in ASEAN’s economic positioning. European leaders, including Ursula von der Leyen and Emmanuel Macron, are planning visits to Vietnam to strengthen ties amid uncertainties in U.S.-Vietnam relations due to potential tariffs imposed by the United States. This initiative aims to create new trade opportunities and investment prospects with trusted partners (Reuters, 2025).

Additionally, shifts in global supply chains have led shipping firms to reevaluate operations in the region. Companies are discreetly moving operations out of Hong Kong and re-flagging vessels due to concerns about Chinese government actions or potential U.S. sanctions in the event of U.S.-China conflict, particularly over Taiwan. This strategic repositioning reflects growing apprehensions surrounding potential U.S.-China conflicts and their implications for international shipping (Reuters, 2025).

Great Power Competition and ASEAN’s Geopolitical Role – ASEAN’s geopolitical strategy focuses on balancing U.S.-China tensions while maintaining regional stability. Analysts emphasize ASEAN’s diplomatic centrality in the Indo-Pacific but warn that internal divisions among member states can challenge its effectiveness (Reuters, 2024). Furthermore, experts analyze ASEAN’s handling of major power rivalries and its policy preferences in response to growing geopolitical tensions (AP News, 2025).

Recent developments underscore evolving security concerns in the South China Sea. Philippine Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro has warned that the Philippines and its allies will counter any attempt by China to impose an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) or restrict flight freedoms over the South China Sea, signaling a shift toward more assertive regional security postures (AP News, 2025). Concurrently, U.S. trade policies and military presence continue to influence ASEAN’s strategic decisions, as the United States maintains its defense arrangements with the Philippines and emphasizes its commitment to regional security (Reuters, 2025).

While these studies provide valuable insights into ASEAN’s rise, gaps remain in understanding how ASEAN can enhance its institutional efficiency and navigate shifting global economic landscapes. This study aims to bridge this gap by integrating economic, geopolitical, and institutional perspectives to assess ASEAN’s evolving role in the multipolar world order.

Methodology

This study employs a qualitative research approach to examine ASEAN’s rise as a geopolitical and economic power in the multipolar world order. The research methodology is structured around three key dimensions: economic integration, geopolitical strategies, and institutional frameworks. By using a combination of document analysis, case studies, and comparative analysis, this study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of ASEAN’s evolving role.

Research Design: The study adopts a descriptive and analytical approach, focusing on ASEAN’s institutional development, economic initiatives, and geopolitical strategies. Primary and secondary sources are utilized to evaluate ASEAN’s impact on regional and global governance structures.

Summary of Findings

This study has explored ASEAN’s geopolitical and economic rise within a multipolar world order framework, analyzing its economic integration, strategic diplomacy, and institutional challenges. Key findings indicate that:

- Economic Integration – ASEAN’s economic initiatives, such as the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), have solidified its role as a major economic hub. However, economic disparities among member states and over-reliance on external markets remain significant challenges (Wrobel, 2019). Compared to the European Union (EU), ASEAN’s economic integration remains less cohesive due to weaker regulatory frameworks and enforcement mechanisms.

- Geopolitical Strategies – ASEAN has effectively maintained diplomatic neutrality in the U.S.-China rivalry through platforms like the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the East Asia Summit (EAS). However, internal political fragmentation among member states weakens ASEAN’s ability to present a unified strategic vision (Egberink & Van der Putten, 2010). The African Union (AU), by contrast, has made strides in collective security governance, which ASEAN could learn from in terms of coordinated geopolitical responses.

- Institutional Limitations – ASEAN’s consensus-based decision-making is both a strength and a weakness. While it fosters regional cohesion, it also results in slow policy implementation and limited crisis response mechanisms, as seen in its handling of the Myanmar coup and the South China Sea disputes (Purbantina, 2015). The EU’s majority-vote system, in contrast, allows for faster policy action, highlighting potential lessons for ASEAN’s institutional reforms.

- Democratic Governance – ASEAN’s non-interference policy limits its ability to promote democracy and human rights, particularly in authoritarian-leaning member states. However, survey results indicate a growing public demand for stronger enforcement mechanisms in ASEAN’s institutional governance. The AU’s African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance (ACDEG) provides a comparative example of how regional bodies can actively engage in democratic promotion.

Discussion and Analysis

Economic Integration and Challenges: ASEAN has emerged as a key player in the global economy, driven by initiatives such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) (ASEAN, 2021). These frameworks aim to enhance trade facilitation, regulatory coherence, and regional competitiveness (Petri & Plummer, 2020). However, economic disparities among member states present a significant challenge (Lu, 2024).

| Country Group | Key Characteristics |

| Advanced Economies | Strong financial systems, robust digital infrastructure (Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand) (ADB, 2022) |

| Less Developed Economies | Inadequate infrastructure, limited access to capital, policy misalignment (Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia) (World Bank, 2021) |

Advanced economies like Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand benefit from strong financial systems and robust digital infrastructure (ADB, 2022), while less developed nations such as Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia face constraints related to inadequate infrastructure, limited access to capital, and policy misalignment (World Bank, 2021). Bridging these gaps requires targeted investments in digital connectivity, financial inclusion, and capacity-building initiatives (ASEAN, 2023). Furthermore, addressing non-tariff barriers and enhancing labor mobility within the region are crucial to fostering a truly integrated ASEAN market (OECD, 2020). The EU’s Single Market provides a model for ASEAN to improve economic integration by enhancing labor mobility and regulatory harmonization.

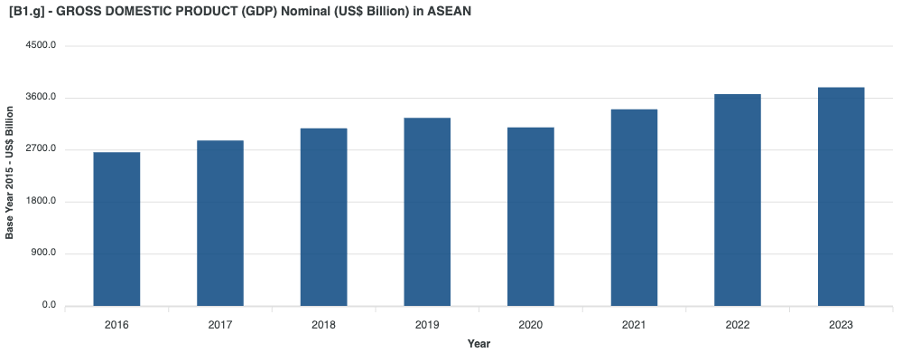

Figure 1: ASEAN GDP Growth Rates (2016–2023).

Source: ASEAN GDP (nominal and growth rates in Chart)

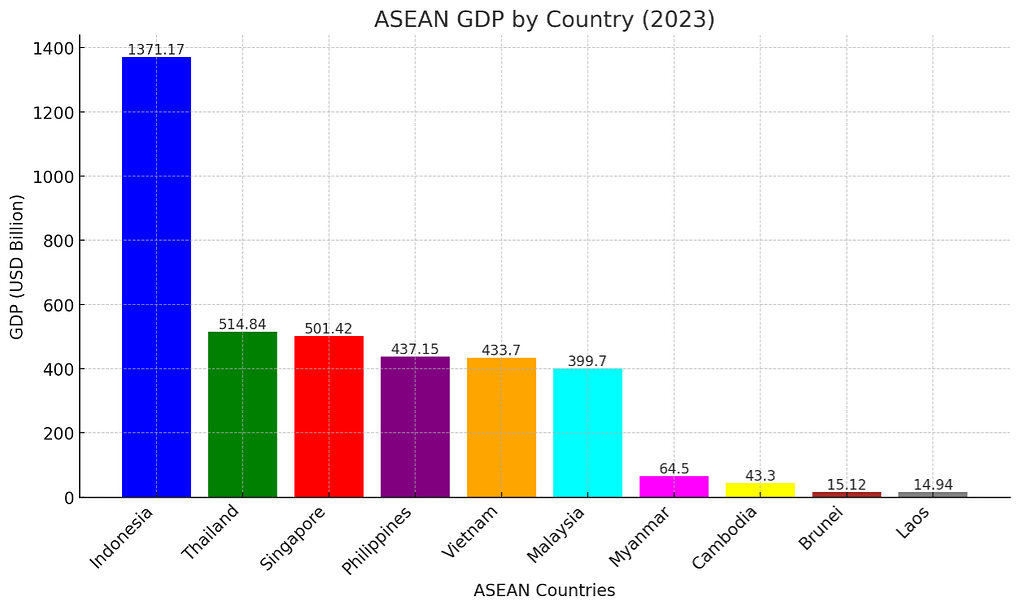

Figure 2: ASEAN GDP by Country (2023) in USD Billion.

Source: List of ASEAN countries by GDP

Geopolitical Strategies and Regional Stability: ASEAN’s geopolitical landscape is complex, requiring strategic navigation between major global powers, particularly the United States and China (Acharya, 2018). The South China Sea dispute remains a focal point of regional tensions, with conflicting territorial claims among ASEAN member states and China (Buszynski & Roberts, 2015). Despite ASEAN’s diplomatic efforts, including the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and ongoing negotiations for a binding Code of Conduct (COC) (ASEAN, 2022), progress has been slow due to differing national interests (Thayer, 2021).

| Key Geopolitical Challenge | Description |

| South China Sea Dispute | Conflicting territorial claims between ASEAN states and China (Buszynski & Roberts, 2015) |

| ASEAN’s Neutrality Policy | Limits strong collective action due to non-interference principle (Severino, 2006) |

| External Pressures | Influence from China’s BRI and the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy (Dosch, 2020) |

Additionally, ASEAN’s commitment to neutrality and the principle of non-interference often limits its ability to take strong collective action (Severino, 2006). External pressures from major economies, such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, further influence ASEAN’s strategic decisions (Dosch, 2020). To maintain regional stability, ASEAN must reinforce multilateral frameworks, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the East Asia Summit (EAS) (Goh, 2019), while strengthening its capacity for conflict resolution and preventive diplomacy (Jones & Smith, 2021). The AU’s Peace and Security Council serves as an example of how ASEAN could enhance its security architecture.

Figure 3: South China Sea Territorial Claims: A map highlighting the overlapping territorial claims in the South China Sea involving ASEAN member states and China.

Institutional Frameworks and Decision-Making Challenges: ASEAN’s institutional framework is based on consensus-driven decision-making, which promotes inclusivity but also poses challenges in responding swiftly to regional crises (Emmerson, 2008). This model has resulted in delays in addressing pressing issues, such as the Myanmar coup, the Rohingya crisis, and regional responses to global health emergencies like COVID-19 (Storey, 2022). While the ASEAN Charter provides the foundation for governance, the lack of enforcement mechanisms weakens its ability to ensure compliance with collective agreements (Caballero-Anthony, 2014). Moreover, ASEAN’s ability to engage in proactive crisis management is often hampered by the varying political systems and priorities of its member states (Baviera, 2017).

| Institutional Challenge | Impact |

| Consensus-Driven Decision-Making | Delays in addressing regional crises, such as the Myanmar coup and COVID-19 response |

| Weak Enforcement Mechanisms | Difficulty ensuring compliance with ASEAN agreements |

| Political Diversity | Differing national priorities hinder proactive crisis management |

Strengthening ASEAN’s institutional effectiveness requires reforms that enhance decision-making flexibility, promote deeper security cooperation, and empower ASEAN-led initiatives, such as the ASEAN Coordinating Council (ACC) and the ASEAN Human Rights Mechanism. Sukma (2014) emphasizes that ASEAN must undergo further institutional changes to improve its ability to address regional challenges and enhance its integration efforts. Comparing ASEAN to the EU’s qualified majority voting system and the AU’s peace and security mechanisms highlights potential avenues for institutional reform.

By drawing lessons from the EU’s economic integration, the AU’s collective security mechanisms, and other regional frameworks, ASEAN can enhance its decision-making capabilities, economic resilience, and geopolitical influence. The study underscores the importance of institutional adaptability in ensuring ASEAN remains a central player in shaping the future Indo-Pacific order.

Table 1: Decision-Making Mechanisms of ASEAN, EU, and AU:

| Organization | Decision-Making Process | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| ASEAN | Consensus-Based | Promotes unity and mutual respect | Can lead to slow responses and indecision |

| EU | Qualified Majority Voting | Efficient decision-making in certain areas | Potential dominance by larger states |

| AU | Majority Voting | Facilitates quicker resolutions | Risk of marginalizing minority positions |

Note: This table provides a comparative overview of the decision-making processes of ASEAN, the European Union (EU), and the African Union (AU), highlighting their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Conclusion

ASEAN plays a pivotal role in fostering economic integration, maintaining geopolitical stability, and strengthening institutional frameworks, making it a crucial player in the Indo-Pacific region. Through initiatives such as the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), ASEAN has positioned itself as a dynamic economic hub, facilitating trade, investment, and regional connectivity. However, to sustain its relevance and leadership in a rapidly evolving global landscape, ASEAN must address persistent economic disparities, reinforce its geopolitical agency, and enhance institutional effectiveness.

To ensure inclusive economic growth, ASEAN should implement targeted policies that bridge development gaps among member states. Expanding infrastructure investment through mechanisms such as the ASEAN Infrastructure Fund, improving access to digital and financial services, and fostering industrial upgrading in less developed economies like Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia will be essential. Additionally, promoting sustainable development through green energy transition initiatives and carbon-neutral economic policies can strengthen ASEAN’s resilience against environmental and economic disruptions.

Geopolitically, ASEAN’s strategic neutrality remains a core strength, but internal divisions limit its ability to manage regional conflicts effectively. Strengthening ASEAN-led mechanisms such as the East Asia Summit (EAS) and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) with more binding diplomatic commitments can enhance its role in conflict prevention and crisis management. Furthermore, ASEAN must establish clearer guidelines for handling disputes such as the South China Sea tensions by advancing a legally binding Code of Conduct (CoC) with China, ensuring regional stability while upholding international law. Enhancing maritime security cooperation through joint patrols and intelligence-sharing agreements among ASEAN member states would further solidify its regional security posture.

Institutionally, ASEAN’s consensus-based decision-making model, while fostering unity, often hampers timely responses to pressing challenges. To improve governance efficiency, ASEAN should consider introducing a “qualified majority voting” mechanism for critical regional security and humanitarian issues, reducing its reliance on unanimity. Strengthening the ASEAN Secretariat’s mandate and resources, along with empowering specialized ASEAN bodies, can enhance the bloc’s ability to coordinate policy implementation and crisis response effectively.

In conclusion, ASEAN’s future influence will hinge on its ability to adapt to shifting economic and geopolitical realities. By prioritizing infrastructure development, digital transformation, and green economic policies, ASEAN can accelerate inclusive economic growth. Strengthening regional security frameworks and adopting clearer, enforceable diplomatic policies will reinforce its role as a stabilizing force in the Indo-Pacific. Additionally, institutional reforms that enhance decision-making efficiency and policy execution will be crucial for ensuring ASEAN’s continued relevance in an increasingly complex global order. Through these strategic adaptations, ASEAN can solidify its position as a leading regional organization that fosters economic prosperity, geopolitical stability, and sustainable development.

Bibliography

- Acharya, A. (2014). The End of American World Order. Polity Press.

- Acharya, A. (2021). ASEAN and Regional Order: Revisiting Security Community in Southeast Asia. Routledge.

- Asian Development Bank. (2021). Transforming ASEAN: Strategies for Achieving Inclusive and Sustainable Growth.

- Bhasin, N., & Kumar, S. (2022). RCEP and ASEAN’s Economic Centrality: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies, 29(2), 45–62.

- Egberink, F., & Van der Putten, F.-P. (2010). ASEAN and Strategic Diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 29(3), 131–143.

- Purbantina, A. (2015). ASEAN’s Institutional Framework and Its Constraints in Crisis Management. Asian Politics & Policy, 7(4), 567–586.

- Reuters. (2024). Analysts Emphasize ASEAN’s Diplomatic Centrality Amid U.S.-China Tensions.

- AP News. (2025). Experts Analyze ASEAN’s Handling of Major Power Rivalries.

- Reuters. (2025). European Leaders Plan Visits to Vietnam Amid U.S.-Vietnam Trade Uncertainties.

- AP News. (2025). Philippine Defense Secretary Warns Against China’s Potential ADIZ in South China Sea.

- Reuters. (2025). U.S. Maintains Defense Commitments in Southeast Asia Amid Regional Tensions.

- Wrobel, P. (2019). ASEAN’s Economic Growth and Its Dependence on China. International Economic Review, 62(1), 89–102.

- ASEAN Secretariat. (2024). ASEAN’s Response to Myanmar’s Ongoing Crisis: Challenges in Maintaining Unity.